- Investors are still hesitant to put money in Argentina following the country’s primary elections, where current President Macri lost in a surprise result.

- Even though Macri has outlined an economic plan to win back voters, markets are waiting on more clarity from Alberto Fernandez, who won nearly half of the vote in the weekend primary.

- Macri made strides during his presidency to gain the confidence of foreign investors. Investors are worried that Fernandez and his running mate, former president Cristina Kirchner, will undo that progress.

- Read more on Markets Insider.

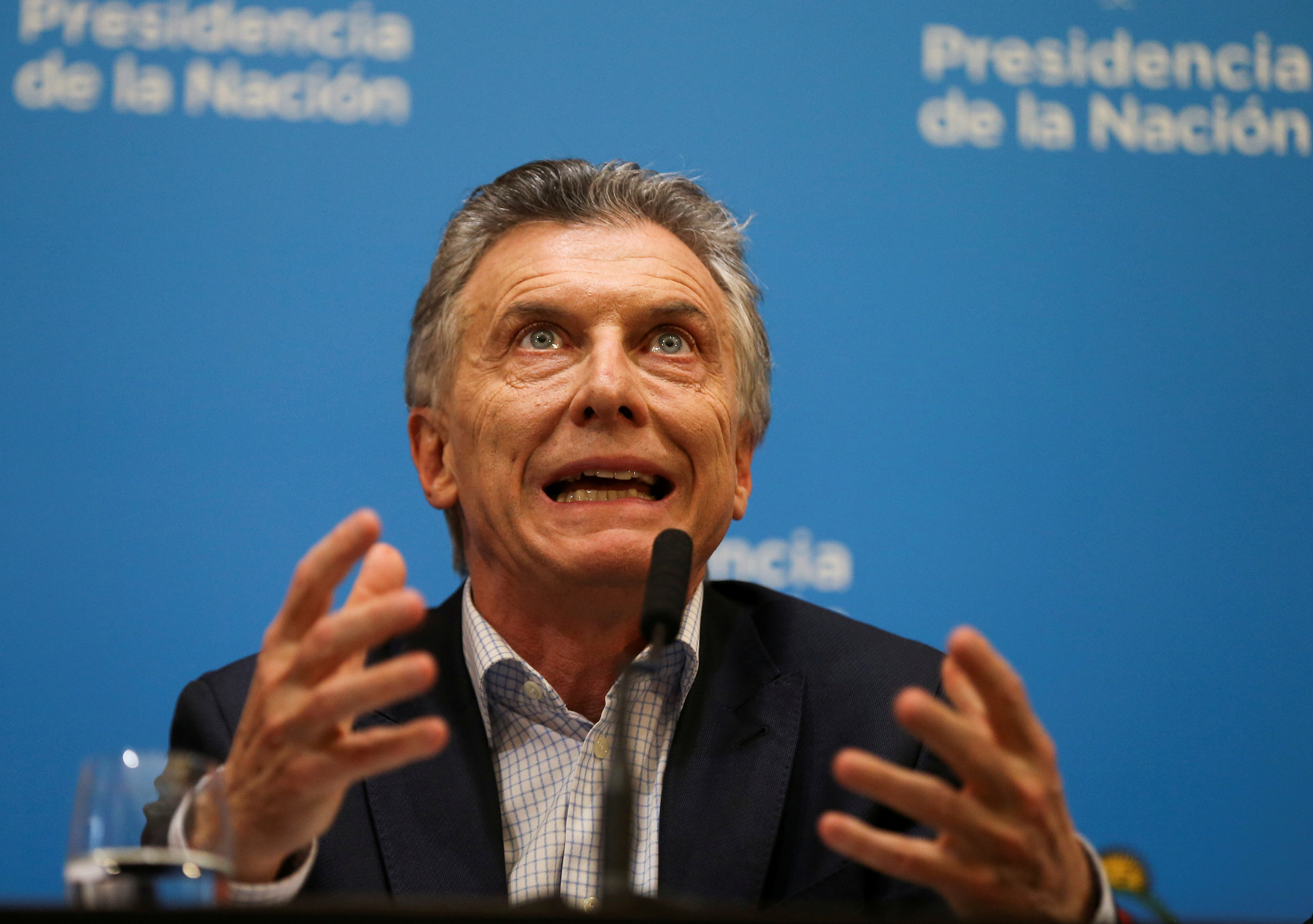

Argentine President Mauricio Macri apologized Wednesday for saying that his opponents in Argentina’s general election would be responsible for market volatility after their surprise win in a primary election over the weekend sent markets tumbling.

Macri also announced several measures to combat recession and extreme inflation in Argentina, the Wall Street Journal reported. His economic plan includes raising the minimum wage and freezing fuel prices for a period of time to help Argentinian consumers.

It was also reported by Bloomberg that he reached out to Alberto Fernandez, the left-of-center politician who is running against him and took nearly half of the vote in the surprise primary victory.

Investors still aren’t convinced. The S&P Merval Index gained slightly since posting the second-largest one day drop ever on Monday, but was still down 32% on Thursday from its position pre-election.

The Argentine peso fell further against the US dollar, and is now at 60.3 to one dollar, a more than 33% slide from last week, when the peso was roughly 45 to one dollar.

"Everyone is anxiously awaiting to get some signals out of Fernandez," said Franco Uccelli, executive director and head of client investment strategy for Latin America at JPMorgan Private Bank in an interview with Markets Insider. "There's a great deal of uncertainty because he has not been particularly forthcoming with his economic plan."

The uncertainty is weighing on financial markets largely because of Fernandez's left-of-center views and his running mate, former president Cristina Kirchner. During her presidency, her administration grappled with many scandals - she's been indicted in 11 corruption cases. They also fixed statistics, limited foreign capital, and relied on subsidies and social programs that proved to be unsustainable, according to the New York Times.

The worry if Fernandez is elected is that he and Kirchner will undo the progress Macri has made since his election in 2015. That includes the largest ever bailout from the International Monetary Fund, worth $56 billion in 2018. If Fernandez wins, he may attempt to renegotiate the country's debts with the IMF, according to Bloomberg.

When Macri was elected, he also made strides courting foreign investors to Argentina by reopening markets. Investment was difficult during Kirchner's presidency in contrast due to her administration's strict control of the Argentine Peso.

There's also the question of default on the table. Argentina massively defaulted on its debt in 2001, which sent the country reeling and took decades to recover from. Under Kirchner, the country suffered a second, much smaller default in 2014. Argentina has billions of dollars of foreign-currency debt due over the next year, according to Bloomberg.

If Argentina does fail to repay its debt, the result would be severe, Uccelli said. "The market would close everything imaginable to Argentina."

So far, there's no indication that Fernandez sees default as a viable option, Uccelli said. "I think the market is generally holding off until there's more clarity on what may happen."

Until then, there is little contagion to the rest of Latin America. Still, if Argentina does spiral out of control, there will be consequences elsewhere, Uccelli said, especially in countries linked to Argentina by trade and tourism.